What we’ve been (un)learning in the social innovation space

This is the third and final part of a three part blog series by Action Lab Founder, Ben Weinlick. Although the blogs can be enjoyed on their own, more richness is gained from reading all three in succession as they build on one another. In the series we move from exploring what we, at Action Lab, mean by innovation and social innovation, to using the “Innovation Swirl” to help us understand the different phases or parts to a social innovation process, to unravelling what phases we think social innovation labs should place the most focus on and finally, we land here - a sharing of some of the learning and unlearning I’ve done in the social innovation space over the years.

See Part 1: What do we mean when we say innovation and social innovation?

See Part 2: Should labs just generate good solutions or incubate and scale them too?

________________________________

What can help bring out good innovation possibilities from a collective?

Methods of our lab processes at Action Lab mainly focus on the Discovery and Experimental phases, although we have had some good success with Edmonton Shift Lab around Performance phase methods to help refine prototypes into pilots after the Discovery and Experimental phases were completed (You can learn more about the Performance phase methods we developed during Shift Lab 2.0 in our final report on our website. Prototype coaches are discussed on pages 84-87 and 130-131).

The “Innovation Swirl”, adapted from Nesta by Mark Cabaj, Here to There consulting

Over the years we have learned some patterns and principles that can help bring out good innovation, particularly in the Discovery and Experimental phases. In essence, a good innovation process is a collaborative problem solving approach that helps a diverse collective make sense of root causes of a complex challenge and then generate possible solutions that can be stress tested with real world people and systems who are affected. We think real system innovation requires more than just a diverse table of people who can talk about issues and ideas in safe ways. Rather than only talk about an issue, a robust innovation process should help to facilitate a diverse collective to make ideas tangible and testable. By testing proposed solutions before investing in pilots (Performance phase), it helps a collective surface assumptions that would have caused bigger problems if left unchecked - ultimately this results in saving money, time and ensuring proposed solutions are relevant. In these processes to come to good innovations we often mix together systems thinking, participatory design methods, Theory U, ethnography, critical theories, participatory action research, and indigenous worldviews (where appropriate and guided by elders and authentic knowledge keepers).

No cookie cutter processes: Every lab process should be customised

We find at Action Lab that every lab we steward is unique and that as a result we have to customise and remix methods for different challenge types, communities, and contexts. In some labs, adapting cultural contexts is very important. Like in the Bhutanese Refugee Employment Lab, we adapted all the process methods with community members from the Bhutanese community. In other labs like the Edmonton Shift Lab, with Elders and Knowledge Keepers, we ethically wove together Indigenous epistemologies, design thinking, systems thinking, and behaviour change science to make the innovation process better in co-creating anti-racism intervention innovations.

We do have some general principles that we believe from experience and literature can help collectives to uncover possible innovations. We have learned that neither systems thinking nor design thinking alone quite cut it. Some processes that only focus on systems mapping, and deep dialogue methods can easily get caught in analysis paralysis, or as I sometimes call it, “existential systems thinking funk”. On the other side, if only using design thinking methods to solve a complex challenge, there can be passionate voices to design for on the ground, but these might miss bigger underlying systemic challenges that don’t get considered or designed for in proposed solutions. We think there needs to be a blend of both systems and design methods - systemic design. In addition, there needs to be real trust and relationship building activities built in because collectives can’t be innovative if there isn’t trust. Fear, and not trusting will stifle creativity, stifle bold ideas, and reinforce the status quo. Not everyone has to agree or think the same - in fact that would not help either, but there needs to be a feeling in an innovation process or lab that everyone has each other’s backs on a team. That is an art to steward well and honestly we’ve learned most from indigenous social innovation colleagues like Jodi Calahoo-Stonehouse and Diane Roussin who constantly remind collectives trying to make positive change that it’s really about relationships - relationships with all interconnected beings and parts in a system. So, I've really learned from these wise colleagues to sometimes let go, throw out the bullet points, sticky notes, and structured processes and dive into being with others - listening and being in a good way. This really is the foundational stuff for all good work and innovations to emerge. I also think it’s important to mention that trust should never just be given or expected, it needs to be earned by action and that takes time if people in a team don’t know each other well. So, you have to build in time for the slower relational work. It’s worth it.

Triangulating insights diagram

Should any innovation process stewards be able to help any organisation, community, or system to work on creative solutions to a complex problem?

Ten to fifteen years ago, I think it was not questioned very much that innovation process or design team experts could simply parachute into any organisation, or community and would have the ability to help regardless of relationships, biases, power and privileges. I know it wasn’t on my radar as much when first learning and experimenting with systems, design and creative problem solving practices in support of the inclusion and belonging of people with developmental disabilities. I think I believed at the time that the creative processes were universal, cross cultural or could be easily adapted to any context. With learning, with making mistakes and having great colleagues to collaborate in good relationship with, I think this has evolved in my own practices and Action Lab practices we steward. But even more so, there is much work being explored in the innovation and social innovation process fields around navigating power, privilege, and equity. Still a ways to go, but conversations of how to be mindful of power dynamics when co-creating with diverse communities are much more prevalent now when stewarding collective problem solving processes. People to learn from around equity and humility practices in collective problem solving processes would be our Shift Lab stewardship colleagues, Diane Roussin, George Aye, and Antoinette Caroll who spoke for our Shift Lab speakers series.

Sometimes an equitable innovation approach might be investing in helping a community struggling with a challenge to build capacity in learning process practises themselves, so community leaders can help their own communities without intervention from outsiders. However, be careful too if this might overburden some communities. We’ve experienced that sometimes communities do want some guidance and support to mix into their own ways of problem solving. I can remember one experience when working with a community where we had funding to equitably compensate leaders to participate in everything - being part of every single co-design planning and delivery meeting. Together we helped community members to bring in their own culturally specific problem solving methods. This was well received at first, and then later on, we had some community members saying “please stop asking us about everything, we don’t know how to make our ideas happen and we need your help.” We built capacity, coached and helped them to generate their own ideas with their own communities, but then there was a sense at a certain point of “please can someone else or some group do this on our behalf, we need some help.” This was a conundrum to navigate that continues to be tricky with these processes, applied even in equitable ways to complex community challenges.

At Action Lab we try to listen, think, reflect on privileges, be critical and sense real hard whether it’s appropriate to have our main stewardship group of Action Lab steward an organisation or community through an innovation process or whether we need to co-steward with a diverse leadership group from a community or system we are working together with. With Edmonton Shift Lab for example this looked like 5 diverse stewards co-designing all the Discovery, Experimentation, and Performance phase processes, and at the same time always adapting and being responsible together. We also always insist at Action Lab that funding for a lab includes equitable compensation for marginalised community members that may be involved in an innovation process. There are also ethics to consider when coming into an organisation or community and getting people excited about collectively tackling a complex challenge people and community have been struggling with. Don’t over promise if you can’t deliver, be clear on expectations and make sure to not leave people hanging, include people in creating hopes for the exploration and surface tensions together that will be navigated together. Don’t be extractive. Be transparent and collaborative. Strive to commit to being in a good relationship with everyone the process connects with. There will never be a simple formula for navigating these tensions, but we try to avoid getting caught in extremes, open our mind to others and be ready to let go of processes we used successfully with one group that may not work or land with another one.

Some general innovation process principles to consider:

A process needs to include activities that help a collective trust each other and build good collaborative relationships

Strong processes help identify and constructively navigate power dynamics in all the innovation phases

It can be helpful to have a small stewardship and/or advisory team that helps guide, design equitable engagements, curate, facilitate, help keep the process and team(s) moving forward and learning

Ensure there is funding for equitable compensation of marginalised groups or people that are involved in any phase of the innovation process

Robust processes for individuals and collectives to make sense of the problem they’re working with. This usually involves some curated literature and data, system sensing, mapping activities, interviewing, ethnography, individual and team reflective practices, and making time to be in good relationship to hear deeper insights around what’s emerging and how to support each other in good learning

Ways to identify what insights from the sense making need to be considered when coming up with innovations

Creative processes for ideation, prototyping and testing of proposed solutions, including adapting or translating them for diverse cultural contexts

Recommendations that come from testing that either signal to try again, keep testing, or what might be required to turn a proposed idea into a pilot or scaling innovation

Some forms of reflective practice and evaluation on what is being learned about the nature of the problem being tackled, prototyping testing and evaluation, and the creation of a relevant learning report. Learning reports and evaluation may be oral storytelling, may be curations of writing, may be short films or other creative means that are grounded in the wishes, cultural contexts and accessibility needs of the group one is co-designing and innovating alongside.

What we’re learning and unlearning these days to make innovation processes better

We and fellow lab practitioners across Canada and beyond are constantly thinking and rethinking processes to make them more adaptable, inclusive, equitable, and better at bringing out the best ideas from a system or community that needs solutions to a tough problem. Without going into all the details, some themes of what we’re grappling with these days related to improving solution finding processes are below.

Innovation is not all about the new, both in outcomes and process. Learn from traditions, and indigenous knowledge of collective community problem solving.

Recognize that if being too rigid with, for example a 5 step design thinking innovation process, it might make people coming from worldviews steeped in oral traditions and non-western epistemologies feel lost or disconnected in the process. We love the idea that has been shared with us by knowledge keepers like Hunter and Jacquelyn Cardinal (Naheyawin) that in some indigenous traditions there is the concept of holding Two-eyed Seeing: holding western and indigenous views without privileging one over the other

We steward the Action Lab on Treaty 6 territory and think about how in all our lab explorations we can steward being better treaty relatives. This means taking time to be in good relationship with everyone involved in a lab exploration.

Being “Human Centered” in a design or innovation process actually might be short sighted from indigenous worldviews. Our close friend, colleague and leading Indigenous social innovator Jodi Calahoo, says “Indigenous communities think and act in systems, and recognize the interconnectedness of land, water, people, the winged and four-legged ones.”

Center lived experience of a system you’re trying to innovate around, but also you need to learn from perspectives of the whole system - even parts of a system you might be biassed to not wanting to hear from.

Labs are generally well suited for robust discovery and experimentation with collectives to find good innovation and solution possibilities. Often due to funding and lack of understanding of what it takes to move a roughly tested idea to full implementation, there can be disappointment if an idea doesn’t move quickly from the experimentation phase to performance phase. Lots of learning and field building with this tension needs to happen collectively to get better at this.

“Nothing about us without us” is more nuanced and complicated when you actually get into the work of stewarding ideas to action with a community. There are times that asking too much of a marginalised community overburdens and does more harm than good. In my idealistic youth, and influenced by ideas of Paulo Friere, I thought the most marginalised just need to be included in everything to co-create the knowledge and solutions to all complex challenges. This beautiful idea when put into practice has surprisingly at times caused unintended harm by overburdening marginalised folks. No matter how much capacity is strengthened, there is a tough tension in that often people experiencing the pains from a system, don’t necessarily have ideas for designing policy, systems and services that are less harmful and more empowering. Again, at present it seems what can help is having a “both-and” mindset and not clinging to extreme idealism when in relationship with others in the real world tackling tough systems together. Include diverse perspectives from a system in co-creation and strive to not overburden. Be a good steward and use any power you have to lift others up and support.

What I’ve shared here are experiences and insights from being in relationship with people, leaders, communities, and organisations we learned with when tackling wicked complex challenges together. There is still so much learning and unlearning that needs to take place in the innovation and social innovation stewardship spaces to keep improving together.

If the work seems overwhelming at times, I’ve found it takes a deep breath, grabbing some friends and jumping into the ambiguity by boldly learning-by-doing together. This might mean starting a project together on a shared systems change issue you all want to tackle.You won’t know how to do it, or how to fund it at first, but it takes this leap. I think the worst thing we can do is to let ourselves get frozen on the sidelines analysing because of being scared of doing the wrong thing. Don’t try to make a difference to please others, don’t try to be a saviour, don’t do it for recognition, power or influence. Do a good try at tackling complex challenges with others because we need each other all working on improving systems for the people and planet. It’s messy, your ego will get bruised, you will learn things and then as soon as you “get” something, you have to let it go and be responsive in the next learning loop. But in the process you might help others, they might help you and you’ll surely be able to look yourself in the mirror in the end because you didn’t take the safe route, but took some responsibility and tried to make a difference alongside others we share this world with.

In sharing some of my learning and unlearning on innovation/social innovation processes from the last 15 years, I hope that some of you reading this won’t have to make the same rookie mistakes I made when striving to be a good innovation steward. You’ll still have to grapple with complexity and it will be hard, but I hope something from these pieces resonates or shakes loose a seed of an idea to build on in your own way. Let us know what you learn as you work on improving systems we’re all connected with in your own ways.

Lastly! Don’t forget awe…

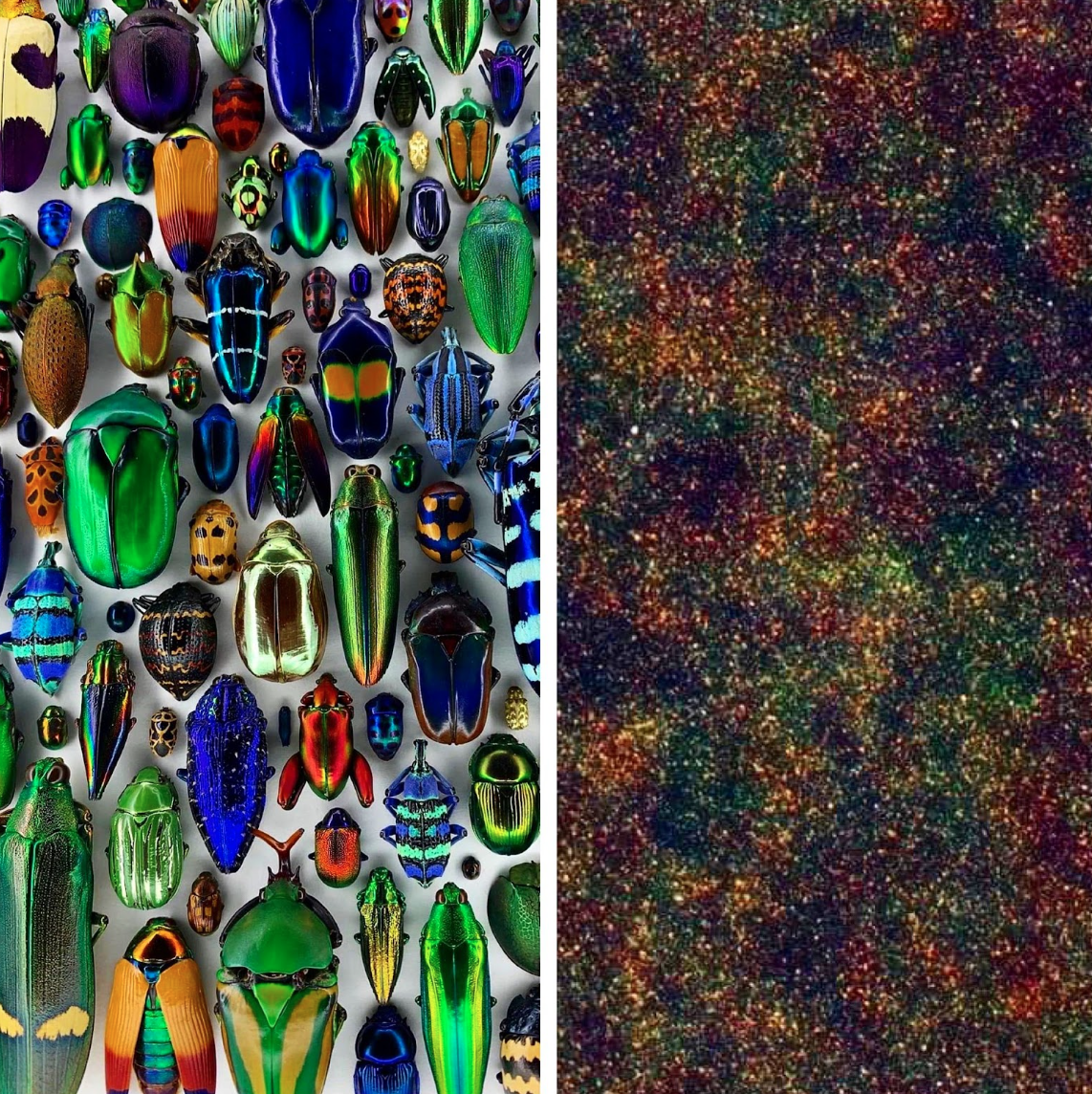

I’ll leave you with the mind blowing tension below that I’m experimenting with. I’m experimenting with ways to spark awe in myself and others, because I think we need more provocations for awe and wonder if we’re going to be helpful in systems change work. If we’re used to deconstructing most of the time, we can easily lose awe and this will affect our creativity negatively. Just sitting with awe and paradox sometimes sparks something fresh.

I mashed together the two pics below of the micro and macro because the juxtaposition simply blew my mind. Two completely different scales next to each other in paradox and yet connected. On the left are amazing green, gold, and pink shiny colored beetles of earth. On the right, each tiny and shiny green, white, gold, pink dot of light is a full galaxy EACH with billions of stars like our Sun. Even across this vast expanse between these two scales, there are interconnections, links and relationships and that’s amazing. I’m not exactly sure how, but something about this paradox relates to systems change paradoxes. Sometimes just letting things be without trying to figure anything out, there can come flashes of aha insights. I hope you find more of those moments and creative collisions ensue.

Beetles and space - representative of the micro and the macro

Choose Awe. Zoom in - Zoom out.

At the very least, strive to be in good relationship with those you are co-creating and innovating with. It matters maybe more than anything else.

A reminder that this is the third blog in a three part series.

See Part 1: What do we mean when we say innovation and social innovation?

See Part 2: Should labs just generate good solutions or incubate and scale them too?

Want to learn more?

Think Jar Collective Social Innovation Lab Field Guide

Join our Edmonton based Systemic Design Exchange community of practice

Check out examples of our innovation and social innovation work in action

ABSI - Alberta Social Innovation Connect

References and Good Sources on Social Innovation

Think Jar Collective Social Innovation Lab Field Guide

McConnell Foundation 2018 12 lessons shared on Social Innovation

Social Labs - McConnell Foundation

Thanks for reading! Follow us on social media @ActionLabYEG to see future posts.